Backpressure in Client-Server Applications

Backpressure, in client-server applications, is accomplished when a client adjusts its transmission of messages in response to a server that has slowed its processing of messages.

Stuck in Traffic

Ideally, when a networked client connects to a server, messages are sent at maximum speed and responses are likewise returned quickly. To handle more client traffic we scale horizontally by adding additional server instances and our long-tail latency metrics are stable over time. However, in most real world applications the server is not a monolith unto itself and will make internal requests to relational databases and external APIs with unpredictable performance characteristics.

Timeouts are essential for achieving resiliency. When a timeout is reached, the client disconnects and potentially tries again until it gives up. The absence of sensible timeouts results in resource consumption (e.g., network sockets, memory, threads) and conditions resembling a traffic jam. In a healthy system both the client and server will monitor connections and proactively timeout.

Constantly connecting and disconnecting, in the face of server instability, has a cost. On average, it takes longer to establish a network connection, and negotiate a secure socket, than to issue requests and responses. An alternative is for the client to respond to backpressure from the server by keeping the connection open and only sending data when the server is ready to accept it. Instead of a chaotic traffic jam, the stream of messages is like a cargo train, with slow-downs anticipated.

Backpressure

The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) considers backpressure as part of the specification. “Understanding TCP Protocol and Backpressure ”¹ does a nice job summarizing the key ideas.

- TCP implements flow control to ensure that the sender does not overwhelm the receiver with data. It uses a sliding window mechanism to control the number of unacknowledged segments that can be sent at a time.

- The receiver advertises its window size, indicating the amount of data it can currently accept.

- The sender adjusts the rate of transmission based on the receiver’s window size, ensuring efficient data transfer.

In practice, for backpressure to work effectively, both the client and the server should adhere to some specific design principles:

- Client & Server

- Connection should be long-lived (e.g., HTTP keep-alive, websocket, etc.)

- Client

- Networking libraries should indicate when the socket is writable

- Timeouts should be tuned to allow for backpressure

- Server

- Separate thread-pools should handle,

- Accepting network connections

- Sending and receiving data over established connections

- Slow or idle clients should be detected and pruned

- Separate thread-pools should handle,

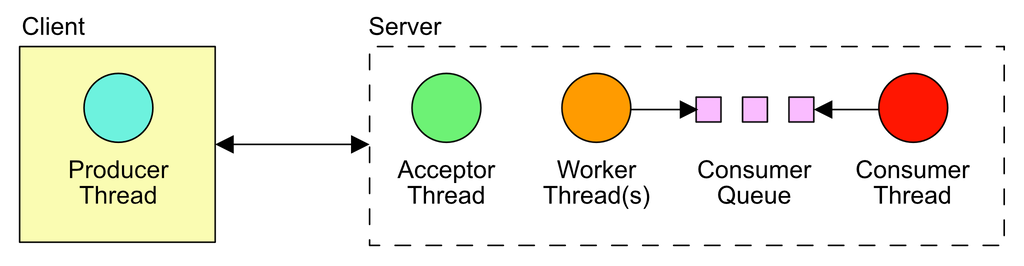

Let us consider an asynchronous, event-driven application architecture. On the server a single thread can effectively handle the job of accepting network connections. Once connected, another thread, or pool of threads, can read requests and send responses. These "worker threads" must take care not block on I/O or mutexes. We read the request data, make asynchronous calls to internal services, and during those asynchronous calls our worker threads may service other requests. Once our asynchronous work is complete, and if the client is still connected, we write a response. This could be backpressure at work, but how can we know for certain? Unfortunately, most of us use software frameworks that make it difficult to know what is going on beneath the surface.

An Experiment

For this article we created a project at https://github.com/travishaagen/blog-backpressure. It's only dependency is Netty, which is an event-driven abstraction over Java's internal sockets and byte buffers. To prove to ourselves that backpressure is occurring, the application establishes a single websocket connection. The client has a Netty event-loop with a single thread. Likewise, the server has a single-threaded connection acceptor and a single threaded worker-pool, which attempts to write to a bounded queue of size 1. A consumer thread reads from the bounded queue at a slow rate. When the queue is full, we cannot write to it, so we stop reading data. When we stop reading, the client is informed that the server cannot accept more data, which causes the client to stop writing. This is backpressure.

Every network connection establishes a

Channel. A Channel

has a method called isWritable() with the following documentation,

Returns

trueif and only if the I/O thread will perform the requested write operation immediately. Any write requests made when this method returnsfalseare queued until the I/O thread is ready to process the queued write requests.WriteBufferWaterMark can be used to configure on which condition the write buffer would cause this channel to change writability.

In our WebSocketClient you can see that, in a loop, we increment a 64-bit integer and only write it to the channel

when writable. The client is detecting and adapting to a full write buffer.

while (!group.isShuttingDown()) {

// will not write, when the write buffer watermark is full

if (ch.isWritable()) {

var buf = allocator.buffer(Long.BYTES, Long.BYTES);

buf.writeLong(writeCounter++);

var frame = new BinaryWebSocketFrame(buf);

ch.writeAndFlush(frame);

} else {

// we're in a spin-loop, so yield to other threads

Thread.yield();

}

}

On the server, to control our experiment, we create a bounded queue of size 1.

var consumerQueue = new LinkedBlockingQueue<Long>(1);

We then pass the queue to a "consumer thread" which reads from it at a slow pace, to simulate a backlog of work.

while (true) {

var value = consumerQueue.take();

// simulate consuming the queue more slowly than the incoming event rate

Thread.sleep(0, 250_000);

}

We also pass the queue to our WebSocketFrameHandler. It reads from the Channel and will spin in a loop

until it can write to the queue. It does not perform any additional reads until the data is written, which causes

backpressure.

var msg = frame.content().readLong();

if (!consumerQueue.offer(msg)) {

while (!consumerQueue.offer(msg)) {

// yield to other threads while we try to write to the bounded queue

Thread.yield();

}

}

When we run the application we'll see an output similar to the following. The Wrote lines show the number of messages

written to the socket and Consumed shows the count of messages read by the server's "consumer thread".

Note that, to save space, only the last consecutive Wrote/Consumed lines are shown below.

% ./gradlew runApp

> Task :runApp

Consumed: 0

Wrote: 100000

Consumed: 60000

Wrote: 120000

Consumed: 85000

Wrote: 150000

Consumed: 105000

Wrote: 170000

Consumed: 125000

Wrote: 190000

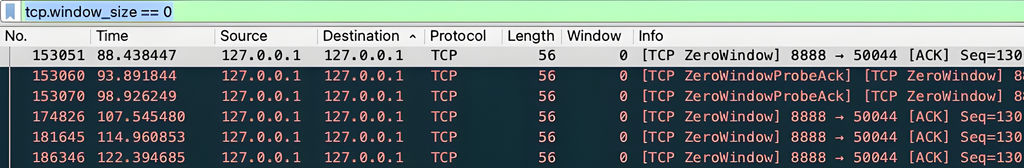

When we observe the loopback interface in Wireshark and set the filter to

tcp.window_size == 0 we see that the TCP window drops to zero multiple times. This is what causes the client to stop

writing.

Final Thoughts

Backpressure is an elegant concept in computer networking. As the above experiment shows, both the client and server need to actively control reading and writing socket data for it to work properly. Websockets seem particularly well suited to applications that seek to control backpressure, because it's easy to conceive of inbound messages feeding into one queue and outbound messages into another. We hope that this discussion will assist developers in thinking about backpressure and how well their libraries and frameworks support it.

For further reading we suggest “Applying Back Pressure When Overloaded ”² by Martin Thompson.

References

- Kumar, A. (2023, August 6). Understanding TCP Protocol and Backpressure. Sum Of Bytes. https://sumofbytes.com/blog/understanding-tcp-protocol-and-backpressure/

- Thompson, M. (2012, May 19). Applying Back Pressure When Overloaded. Mechanical Sympathy. https://mechanical-sympathy.blogspot.com/2012/05/apply-back-pressure-when-overloaded.html